This part of the exhibition builds on archive materials and compares fisheries development efforts of the Norwegian government in two very different parts of the world. First, it considers the way it tried to rebuild the fishing industry in northern Norway (Troms and Finnmark region) following the devastation of World War II. Second, it describes the first UN-supported development project, known as the Indo-Norwegian Project (1952-1972), which was implemented by the government of Norway in southern India soon after its Independence, when food shortages were omnipresent.

It was accompanied by a large public campaign to raise money in Norway and became very well known. The INP-project also, however, was severely criticised. Some observers have therefore concluded that the project did more harm than good. As the re-development of fisheries in northern Norway was carried out in the same period as the INP-project, and many of the leading people involved in both efforts were the same, it is useful to compare the two.

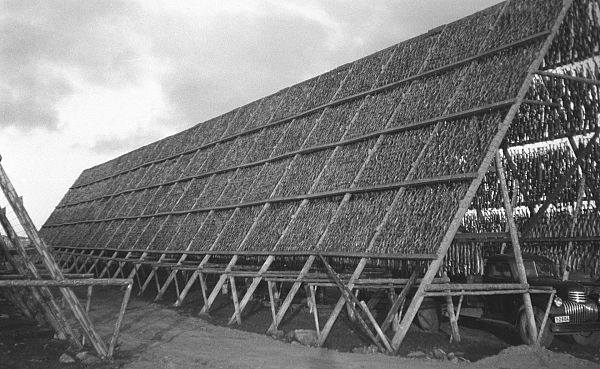

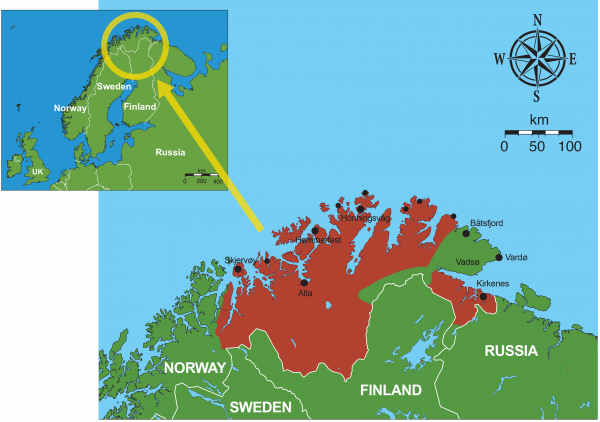

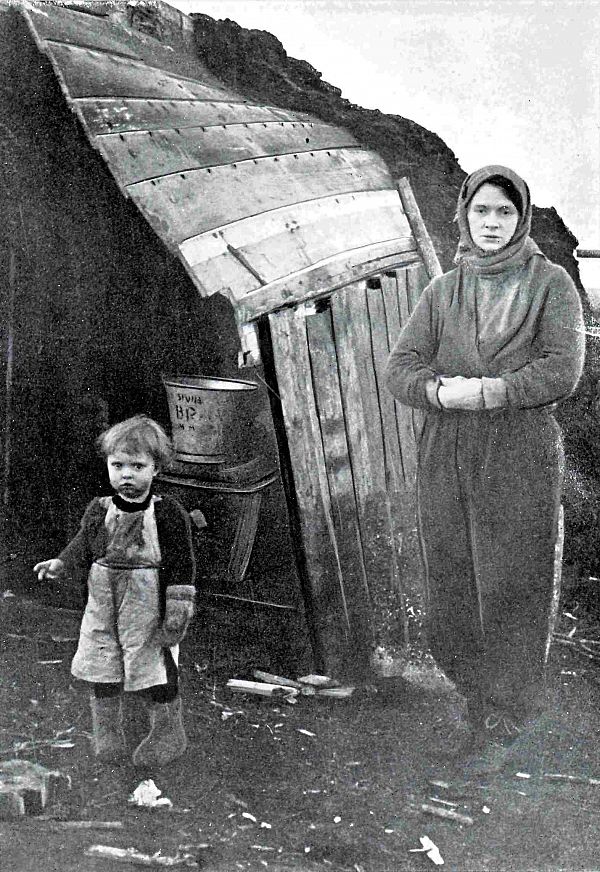

Following the Second World War, the Norwegian government was concerned about rehabilitating damaged areas far north, which had been destroyed. After all, in the autumn of 1944, German troops withdrew from the northern parts of Norway, destroying everything in their way (this is known as a scorched earth strategy). About 50,000 people became refugees in their own country, and most of them belonged to settlements along the coast. In Troms and Finnmark counties, small-scale fisheries had always been the backbone of economic life, and this sector was hit hard. About 350 larger coastal vessels were destroyed, and several thousand open boats. As many as 260 fish plants were devastated (figures for Finnmark county alone). Most of them were small plants that processed catches into fresh-packed fish, salted fish, and dried fish products. After the war, the Norwegian authorities focused not only on the rebuilding of damaged coastal villages but also on the modernisation of the fisheries. The overall goal was more or less the same as for the INP-initiative: to improve the living conditions of the fishing population by use of new and better technology. In North Norway, however, the government did not introduce trawling in a significant way, while the technology itself was considered viable. Instead, it focused on modernising the processing industry. A huge programme for the establishment and implementation of frozen fish technology was passed in Parliament, and from the early 1950s, several fillet plants were erected along the coast.

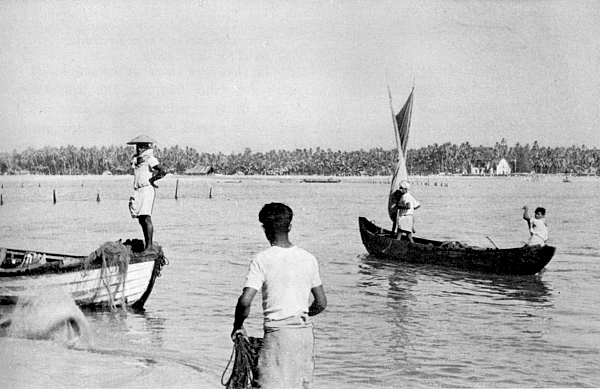

Meanwhile, the newly independent Government of India was trying to deal with its problems. The country was poor, food was in short supply, and the fisheries were underdeveloped. Modernisation was therefore considered important, and the INP-project was to contribute to this effort. The governments of India and Kerala agreed to establish the INP-project in the village of Neendakara, along the southeast coast of the country, in one of its prime fishing regions. Fishers along this coast had been practising fishing for thousands of years, making use of relatively simple but appropriate beach-landing craft. In the first years of its existence, the Norwegian experts from INP who had settled there aimed to equip these craft with engines – an effort that failed quite miserably.

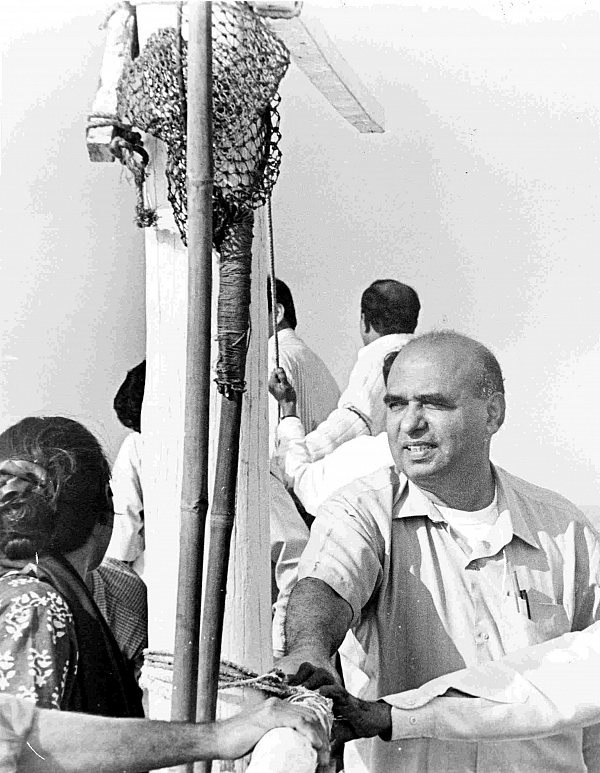

At the end of the 1950s, they changed their approach, focusing on establishing a simple trawling industry that was to operate alongside the existing fishery. The Norwegian experts experimented with boat designs and operating practices, trained fishers in their use and attempted to establish new marketing channels. This time, they happened to be lucky: not only had large shrimp stocks just been discovered off the coast of Kerala, but private traders had also established new seafood export channels to the USA and other countries. As people could now benefit from catching shrimp and exporting them, many people started investing in trawlers. After a while, however, the growth of the trawling sector led to enormous conflicts with the large population of small-scale fishers. The latter felt threatened by the trawlers catching ‘their shrimp’ and regularly destroying their fishing gear, which led to the rise of a national fisher movement, now known as the National Forum of Fishworkers (NFF). A Catholic priest named Thomas Kocherry played an important role in organising protests against the trawling sector in Kerala.

While the INP played an important role in establishing trawling in India, their involvement with village fisheries stopped in 1963 when facilities in Neendakara were transferred to the government. From then on, the INP operated boat-building yards and other facilities in three coastal centres: Karwar (Karnataka state), Cochin (Kerala state) and Mandapam (Tamil Nadu state). At the project’s closure in 1972, the Government of India released a statement saying: ‘With its programmes […] the Indo-Norwegian Project has opened out the vistas of new horizons’ (Government of India 1972). Others, however, have been far more critical (Kurien 1985; Galthung 1969).

There are both significant differences and interesting similarities between the two regions that we are comparing – the war-damaged parts of northern Norway on the one hand and the INP project in India on the other. In both areas, the traditional coastal fishery was regarded as ‘backward’ and in need of modernisation. Both programmes had great impacts. In northern Norway, the implementation of industrial processing methods on a large scale increased the demand for a steady supply of fish to the fillet plants. However, the existing fleet of inshore and mid-shore vessels was not able to provide for sufficient quantities of fish to meet the requirement from the industry. Some technocrats were therefore eager to launch a large trawling programme. However, this was successfully opposed by powerful Norwegian fishers’ organisations. It is worth keeping in mind that north Norwegian fishers had a long tradition of protests against large-scale vessels. Norway also had a very restrictive trawler act that banned trawling within the four nautical mile fishery zone. In addition, it was prohibited for anyone other than active fishers to own fishing vessels. Trawling did become a part of the fisheries in the north from the late 1960s, but never a major part, and only in certain restrictive conditions.

In India, however, coastal fishers did not organise themselves successfully until after the completion of the INP project. The government also did not issue any regulations for trawl fishing until the 1980s. In short, although there were pressures to start trawling in both regions, the availability or non-availability of fisher organisations and restrictive legislation made the difference in how these two fisheries sectors developed.

Bjørn-Petter Finstad, UiT – Arctic University of Norway

Maarten Bavinck, UiT – Arctic University of Norway

Traditional fishing canoes next to few beach-landed boats introduced by Norwegians, India, Kerala, 1960s (Klausen, Arne Martin, 1968)

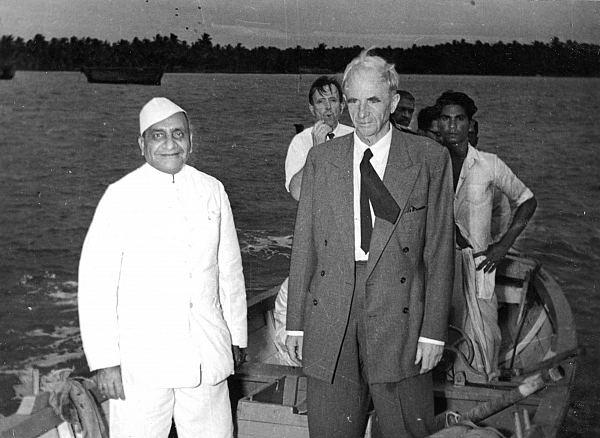

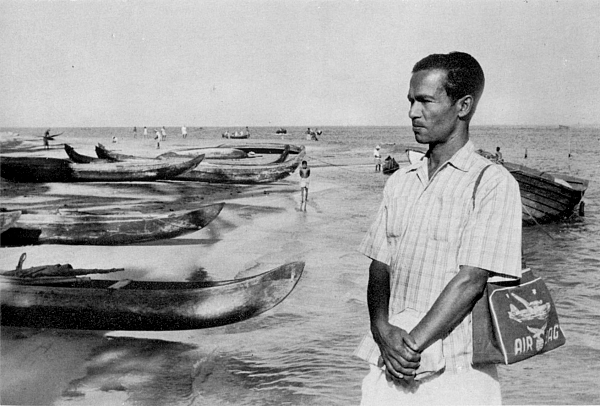

One of the first local fishers to invest in a trawl vessel, India, Kerala, early 1960s (Klausen, Arne Martin, 1968)

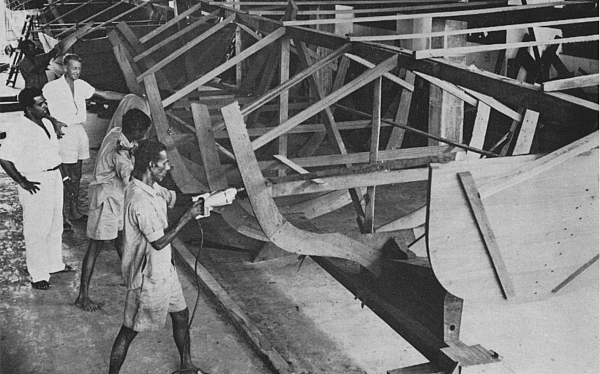

Building mechanized boat under Norwegian supervisors, India, Kerala, 1968 (Source Klausen, Arne Martin, 1968)

Thomas Kocherry, the leader of the new fisher organization, India, Kerala, late 1970s (The Times of India Group)

The locations of destroyed counties in North Norway during WW2 (map by UiT The Arctic University of Norway)

Boat used as home after WW2 destruction, Northern Norway, 1944 (Ole Friele Backer on wikipedia.org)

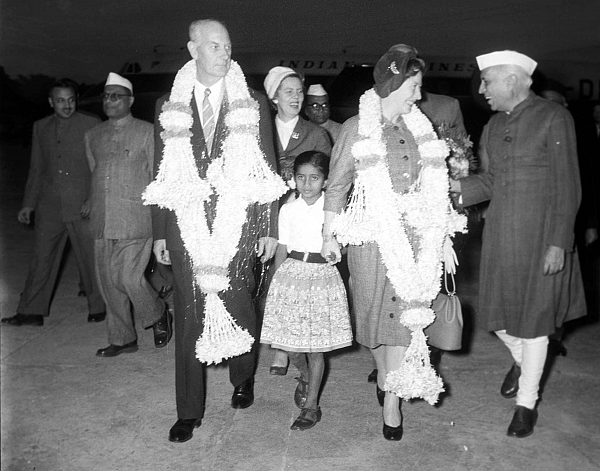

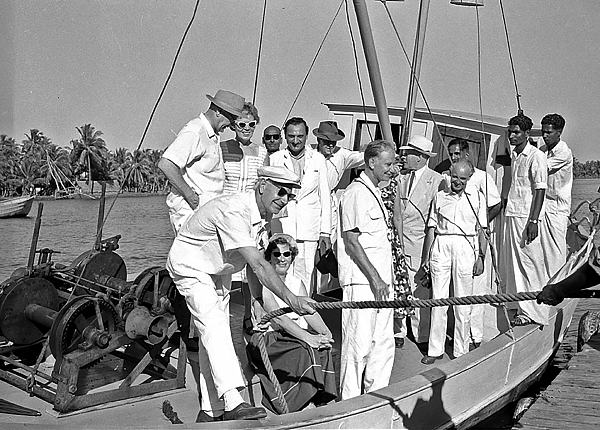

Prime Minister Gerhardsen and Foreign Minister Halvard Lange on modern fishing vessel, India, Kerala, 1958 (Photo by flickr.com)

Fishing fleet Honningsvåg, North Norway, 1947 (Photo by Gunnar Fjermeros, Troms og Finnmark fylkesbibliotek)