Women have been central to the small-scale, household-based fishing enterprise throughout the world. While men go out to sea ‘following the fish’, women take over as soon as the boat returns home, or traditionally this has been the case. Women have been responsible for the trade and distribution and for the drying and processing of the fish catch. Nevertheless, coastal transformations have changed women’s traditional roles, marginalising them in some contexts and opening new opportunities in others.

Women are less visible today as they are not registered as boat-owners or fishers, yet their contribution to fishing households remains as significant as before. Gerrard and Kleiber (2019) see women as the ‘ground crew’ of the fishing sector, engaging in most land-based fishing tasks, both pre- and post-harvest. Apart from trading and processing fish, they are involved with cleaning boats, washing clothes, gutting fish, raising capital, recruiting labour, engaging with aquaculture and a range of other administrative tasks relating to the boat and crew. They were also centrally involved in the fish processing and canning industry from the end of the 19th century to the 1980s, in the case of Slovenia (Lisjak, 2001). With the disappearance of these factories from local settings, these traditional ‘women’s jobs’ also disappeared. If all these tasks are counted, fisheries could well be seen as a female sector.

As reflected in the lack of data on women’s multiple and varied contributions to the fish value chains, from production to consumption, the invisibility of women is reinforced by their lack of formal rights to boats, gear and indeed to the land and sea. However, gender norms and relations are context-specific. In India, for example, fishing communities are based on unequal, patriarchal power relations, with most women disadvantaged in their access to credit and capital, training and technology, and representation in decision-making and management of the fisheries enterprise. Men are better able to diversify their livelihoods and make strategic life choices, with younger women additionally constrained by restrictions on their mobility, perceptions of risk and lack of time (Lawless et al., 2019). However, older women from boat-owning families, with their wide social networks and access to capital, are finding new avenues for engagement.

For fisheries to be sustainable, it is critical to recognise and value the contribution of women, both direct and indirect (Weeratunge et al., 2010). Such recognition will ensure that fisheries management and development policies do not adversely affect people’s livelihoods, well-being and the environment on which they depend, while at the same time enabling a critical analysis of the relationships between different categories of people and their context.

In India, the state’s focus on blue growth, implying a capitalisation of fisheries and export promotion, has meant the neglect or even subordination of community institutions and their practices for resource management, perceived locally at least as to some extent equitable and legitimate. In Maharashtra, this has driven women out of fishing, yet – given their responsibilities for household management – they are pushed to hard labour in local factories. Though regular, their wages are low. Others engage with home-based work such as making beads, again for a pittance. These women have been transformed from household entrepreneurs and traders into low-paid wage workers. In southern India, trends have been mixed. While some women, more senior and better connected, are able to find opportunities for auctioning and trading fish, a majority are driven to petty vending or gleaning of waste fish for subsistence. Others have withdrawn from the fishing enterprise at least in the public domain, and while continuing to contribute to the management of capital and labour and domestic reproduction, they are seen as ‘housewives’, dependent on their men. This change has meant a shrinking in their autonomy and status in the household and the community.

Also, in the UK and Slovenia, very little data exists on women in fisheries, although we have information to show that women hold a range of important roles within family fishing businesses, from maintaining records and administration to raising capital, arranging sales, cleaning of the fish, and its processing. In Slovenia, some women are involved in aquaculture (e.g., as biologists), small family fish market companies, project offices and tourism; others come back to fishing after finishing their school education and pursuing other careers. However, as elsewhere, research has found that many women working in the UK fishing industry remain undervalued and unrecognised. They provide behind the scenes support to their men both before and after they come back from the sea. As well as looking after the children and running the household, these women perform a range of duties related to the fishing business – from taking orders to bookkeeping; this work can be both unpaid and invisible (Zhao et al., 2013).

Like in the case of Maharashtra, India, women from fishing households and communities in the UK and Slovenia are increasingly taking up employment outside of fishing to support their families, some even becoming ‘primary breadwinners’ of the family (Gustavsson and Riley, 2018). In some cases, this is linked to the decreasing profitability of fisheries due to changing ecological and climatic factors, market dynamics and an unsupportive regulatory framework. However, this raises concerns about the increasing burdens of work on women, where household and childcare duties have remained unchanged.

Nitya Rao, University of East Anglia

Tina Steffe, owner of three fish shops on Slovenian coast (Credit: Jaka Jeraša, Primorske novice)

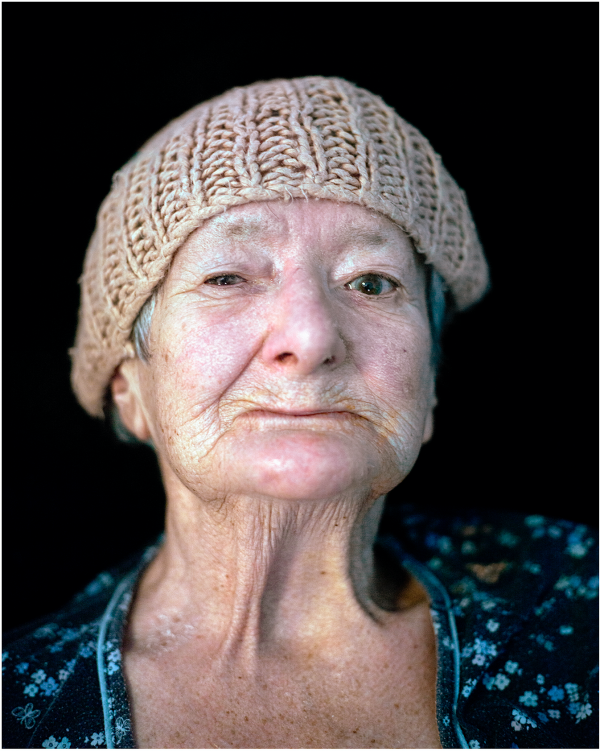

Glynis Skews, a smoker from Lowestoft in 2019 (Credit Craig Easton, 2020)

Fisher girls at work, 1950s (Photo credit: Time and Tide Museum of Great Yarmouth Life, UK)