By following fish from the sea to fishers’ nets, and then to markets and kitchens, the aim is to unpack the spatial, and socio-economic configurations underlying fish’s journey. The stories of species speak about marine ecology, labour, and social relations: they also tell us about chains and paths of fishing, harvesting, and commercialising, as well as about histories of imagination and representation, changes of technology, knowledge and the political economy of fisheries.

The methods of following objects, be they material or immaterial, by tracing them back to their origins, has been gaining importance across several domains of social science. Based on the methodological precepts of anthropologist Ian Cook and colleagues (2004), this approach has helped open up a vast field of reflection. If early efforts of this approach were motivated by the desire to capture global flows of materials and their contribution to building networks of goods, recent efforts have focused more on understanding the non-material and non-human – nature, commodities, tools, animals, and traces (Weber 2014). Such a geography of the ‘more than human’ makes it possible to articulate critical social and cultural geographies pertaining to nature or artefacts (Ibid; Whatmore 2006).

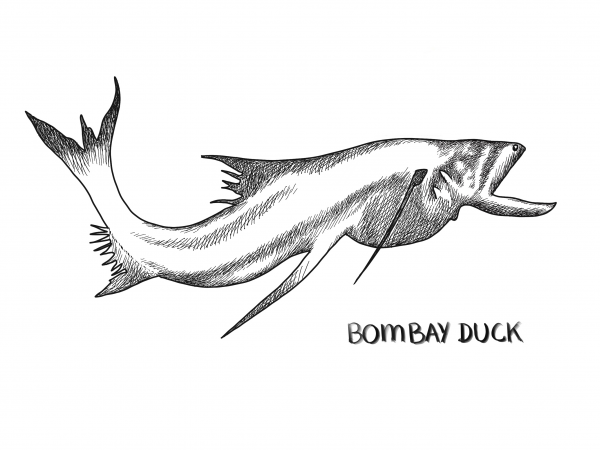

In western India, no species could better represent the stakes faced by small-scale fishers today than Bombil, also known as Bombay duck (or lizardfish). Both due to the increasing industrialisation of the fishing sector and the rapid urbanisation of the Mumbai metropolitan area, this species, one of the most prominent in the region, is a morbid metaphor of the decline of small-scale fisheries and, with it, the slow disappearance of special practices, knowledge and habits. It is also a story of the shrinking productive role of fisher women and their households, highly dependent on Bombil to survive. Ironically perhaps, Bombil today occupies a place of choice as a gourmet dish in many fine restaurants in the city.

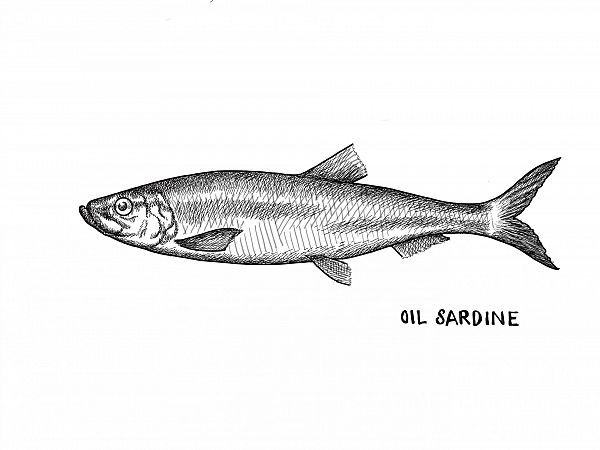

The oil sardine in Tamil Nadu tells a very different story, even if it does have parallels. Little appreciated by Tamil palates, it recently has become central to the economics of fisher households, having migrated from the west coast to the east. To meet an increasing national demand, especially from Kerala, the sardine fishery has undergone abrupt changes, creating conflicts among small-scale fishers because of new gear and fishing techniques. The sardine fishery has brought in investors from outside the fishing community, encouraged small-scale fishers to adopt technologies that favour quantity and quick profits, and undermined precautionary measures cognizant of the environmental impacts of industrial fishing.

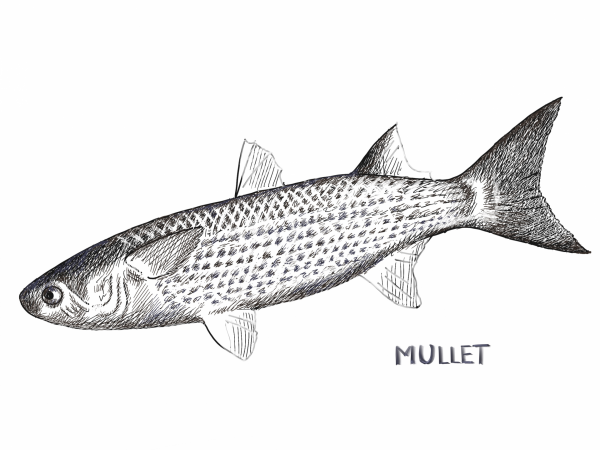

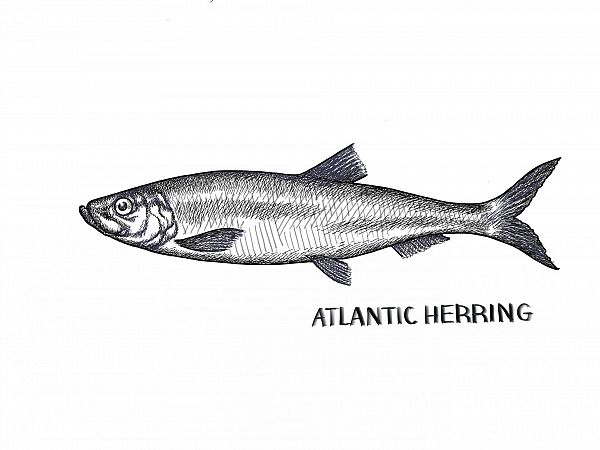

In the European case, the Slovenian Golden grey mullet and the UK herring remind us of the history, identity, and culture of fishing.

In Slovenia, the behaviour of the mullet, ‘known to not let it easily be caught’, tells an untold part of the region’s history, namely that of Italian-speaking inhabitants of the Slovenian city of Piran. The mullet brings to the fore a story of an ephemeral communal life of cooperation around labour and the everyday, but it also highlights the sudden disappearance of this episode post World War II. The mullet and its related history depict the fast-changing environment and the limited resources of the sea, both of which amplify questions of identity and national politics.

Herring’s contribution to the UK’s fishing identity is central. It is at the core of the cultural and economic history of the region, from Scotland to the south-eastern part of England, and is referenced in a whole set of artefacts, literature, and folklore. Its presence is referred to in historical records as early as the 17th century, related to domestic and later commercial fishing practices, as well as the migration of labourers. As in other contexts, the decline of this specialised fishing industry, along with the vanishing of related practices of fish-smoking and processing, narrates fast-changing economies and environments.

Nicolas Bautès, French Institute of Pondicherry