Throughout history, people have depended on oceans and inland waters for food. Fishing is, therefore, one of the world’s oldest occupations. Until the 19th century, the technology used in fishing was limited and relatively simple, with most fishers – men and women – using small boats and various kinds of nets, hooks, and lines. Industrialisation changed all this.

Boat sizes and engine powers increased, and modern equipment was introduced. Small-scale fishing soon became regarded as ‘old-fashioned’ and ‘primitive’. Still, although they started to be forgotten, small-scale fishing fleets did not fade away. In fact, small-scale fishing is now again recognised as an important and environmentally-friendly way of life, contributing to the income, employment, and food security of millions of people worldwide. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) that the United Nations adopted in 2014 mention support for small-scale fishing (see SDG14b). Furthermore, the members of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations have recently adopted guidelines (e.g. Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries in the Context of Food Security and Poverty Eradication, FAO 2014) specifically for supporting small-scale fisheries. Such fisheries are argued to play an important societal role, not only now but also in the future.

Small-scale fishing people, however numerous they might be, are unequally distributed across the globe. In the previous century, their numbers declined significantly in Europe and North America, although even there – as we shall see below – they are still ‘too big to be ignored’ (this is also the title of an influential fisheries research network and knowledge mobilisation partnership funded by the Canadian Social Science Research Council in the period 2013 to 2019). However, in other regions, most notably in Asia and Africa, the population of small-scale fishers has continued to grow, contributing in a major way to economies and to the food security and nutrition of rural and urban inhabitants. Out of the world’s entire motorised fishing fleet, 82% of boats are less than 12 metres in length (many governments and international organisations use the length of fishing vessels as criterion for their classification, with 12 metres often being the cut off point for small-scale fisheries) but in Asia and Africa alone, there are more than 1.5 million non-motorised operators (FAO 2020). All these fishers belong in the category of small-scale fisheries.

The traditional division of labour in most small-scale fisheries is for men to board boats and catch fish, while women are responsible for processing and sale. In many coastal societies, however, women also engage in gathering shellfish and other fishing activities. Children often accompany their parents and gradually learn not only how to swim but also about the qualities of different fish, where they can be found, and how to catch them. By the time they grow up, they have become accomplished fishers.

Although small-scale fishers are skilled and proud of their prowess, they also face many challenges. Climate change is one of them. After all, climate change is associated with rising sea levels and more violent storms. Living on the coast, within proximity to the water, small-scale fishers are the first to experience these phenomena. As lands to the rear of the coast are often already occupied, they cannot easily move their houses. Because of rising sea temperatures, fish sometimes change their behaviour, resulting in fishers no longer being certain about where the fish are. However, perhaps the biggest challenge for small-scale fishers emerges from other initiatives to use the shoreline and the watery environment. Tourist hotels, aquaculture enterprises and wind farms compete with small-scale fishers for space, while industrial fishers compete with them for fish in the water. As small-scale fishers also often have small-scale power, it is not easy for them to turn the tide. International organisations like the World Forum of Fisher Peoples (WFFP), the World Forum of Fish Workers and Fish Harvesters (WFF), and the International Collective for the Support of Fishworkers (ICSF) play a role in defending and improving the situation of small-scale fishers.

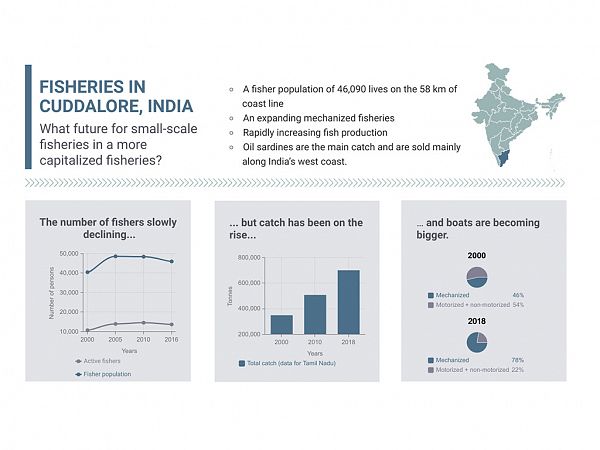

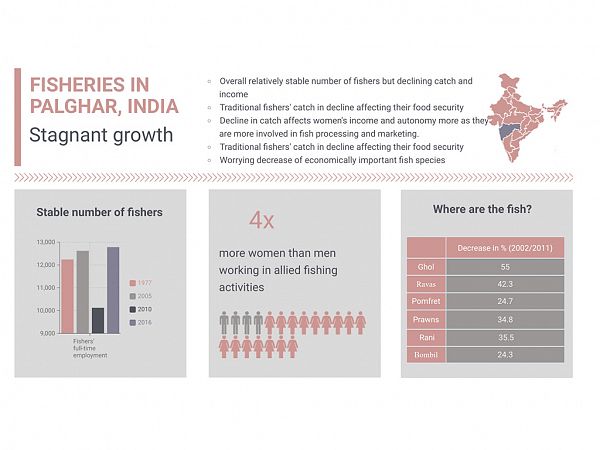

The four countries represented in this exhibition have very different fishing histories, and their small-scale fishing populations possess diverse occupational experiences and prospects. In Europe, on the one hand, small-scale fishers are ‘a forgotten fleet’ fighting for recognition (see Percy, J. and B. O’Riordan 2020. The EU Common Fisheries Policy and Small-Scale Fisheries: a Forgotten Fleet Fighting for Recognition. In: Pascual-Fernández, J., C. Pita and M. Bavinck (eds.), Small-Scale Fisheries in Europe: Status, Resilience and Governance, pp 23-46, Dordrecht: Springer), while along the western and eastern coastlines of India, small-scale fishers are still numerous. Nevertheless, each region has its own dynamics (see for detailed descriptions of the small-scale fisheries of Europe: Pascual-Fernández, J., C. Pita and M. Bavinck (eds.), Small-Scale Fisheries in Europe: Status, Resilience and Governance, pp 23-46, Dordrecht: Springer). In India, small-scale fishing still predominates. Almost 3,500 fishing villages, inhabited by approximately 900,000 fisher families, line its 8,129 km coast. There is, however, enormous variation between them. This exhibition focuses on two coastal regions, one on the west coast (Palghar District) and one on the east (Cuddalore District). In both regions, small-scale fishing is still going strong. The numbers of small-scale fishers, however, have been declining slightly, while trawling has significantly increased. Small-scale fishers complain that catches are declining and that they are being affected by the urbanisation and the industrialisation of the coast.

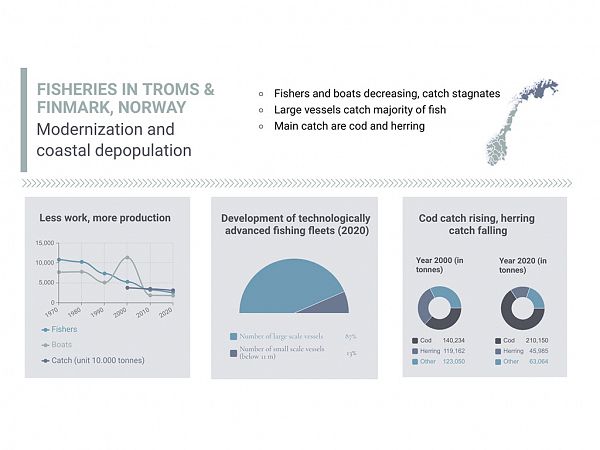

Possessing a long and rugged coastline, Norway is an old-time fishing nation. Fisheries play a strong role in its history and the identity of its population. However, small-scale fisheries have reduced in importance since the early 1990s due to collapses in important stocks and the introduction of new policies. As a result, the number of small-scale fishers has declined severely, which is also the case in Troms and Finnmark county, which is the focus of this part of the exhibition.

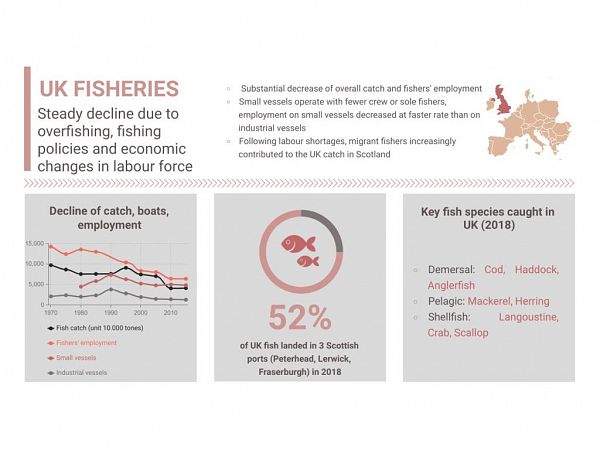

The United Kingdom, located in the North Sea, hosts a large and rich fishing industry, in which 79% of the total active fleet is made up of small-scale fishers. These fishers, however, account for only 11% of the overall landing value, a situation that reflects their restricted access to fish resources. In past decades, the number of small-scale fishers has declined by half, reflecting the ongoing mechanisation of fishing practice and the effects of overcapacity policies.

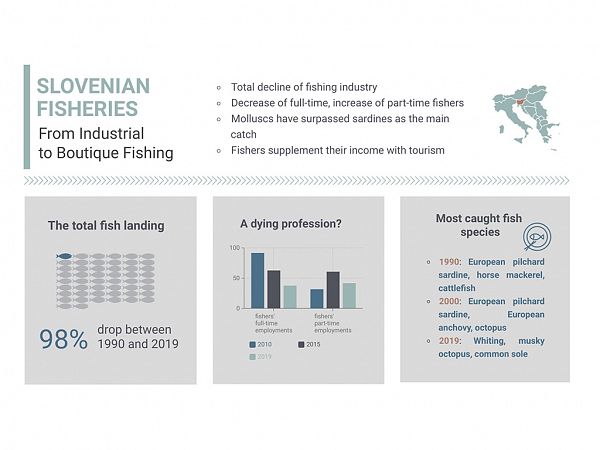

Slovenia is located in the Mediterranean Sea Basin, which has a long and rich fishing history. The small-scale fisheries in this country have been shaped by the dissolution of the former Republic of Yugoslavia and later by joining the European Union and its Common Fisheries Policy. Both transitions have been difficult for fishing families along this shoreline, who have not yet been able to organise themselves properly. The development of tourism and aquaculture in the coastal areas of the country has, however, increased the range of possible income sources.

While small-scale fishers – men, women, children and their communities – face a multitude of challenges – from storms to low market prices and public health disasters – they emerge as enduring figures in the coastal landscape. In this exhibition, we pay them tribute.

Maarten Bavinck, The Arctic University of Norway

Source: Fisheries Department, 2010 and CMFRI 2005, 2010, 2016, 2018.; Infographic by M. Bofulin on Visme

Source: CMFRI 2005, 2010, 2016; Government of Maharashtra 2017; Infographic by M. Bofulin on Vise