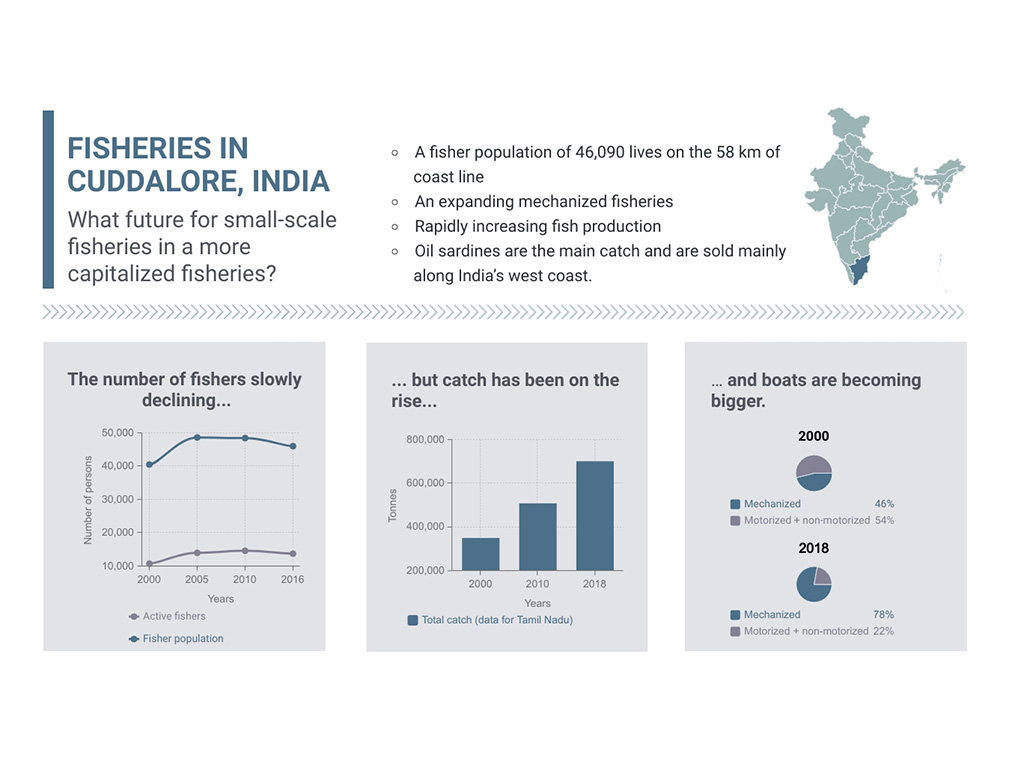

Cuddalore district is located approximately 180 km south of Chennai and is one of the fourteen coastal districts in Tamil Nadu. It has a coastline of about 58 km, stretching from the Gadilam estuary in the north to the Pichavaram mangroves in the south. There are, according to the latest (2016) CMFRI data, 43 fishing villages, 12,988 fishing families (of which 12,577 are traditional fisher families), and a total fisher population of 46,090.

According to this 2016 data, 21,467 people are employed in fisheries, of which 13,812 are active fishers and 7,655 involved in allied activities such as marketing of fish, making/repairing of nets, curing/processing and labour. Many of those employed in allied activities are women.

After the 2004 tsunami, there was a significant upgrading of crafts, engines and nets. In 2010, there were 1,049 mechanised boats and 3,091 small-scale boats (2,255 motorised and 836 non-motorised). Out of the 1,049 mechanised boats, 643 were trawlers, 249 ring seiners (purse seiners) and 152 gillnetters. The number of trawlers increased from 417 to 643 between 2005 and 2010, whereas the number of ring seiners increased from 42 to 249 between 2005 and 2010. There was, however, a decline in motorised and non-motorised small-scale fisher crafts, the result of mechanised craft increasingly accounting for the marine catch. The latest 2016 data, which needs to be tested on the ground, suggests a reversal: mechanised boats have declined significantly to 421, and non-motorised boats increased to 2,016. This increase in non-motorized boats, however, is mostly in terms of feeder boats for mechanized purse seiners or trawlers. Moreover, the mechanized sector accounts for the vast majority of total catch.

The upgrading of crafts and gear post-tsunami resulted in increased fishing capacity at least until 2010, which can be seen in the overall catch from Cuddalore OT (main harbour) and Devanampattinam, where the total catch increased from 19,782 tonnes in 2001 to 64,973 tonnes in 2010. Oil sardines accounted for close to 75% of total catch and steadily increased between 2001 and 2010. While there is no available comparable data for earlier periods, it appears that other fish such as silver bellies and perch were more prominent in 1980 for trawl fisheries and seer fish and elasmobranchs (sharks/rays) for gillnetters. Small-scale fishers are worried that increased capacity has resulted in severe depletion of marine resources. Not surprisingly, conflicts between purse seiners and small-scale fishers increased significantly, although recent data and field insights suggest that they might now be on the decline. What the secondary data do not capture fully is the increasing contribution of non-fishing livelihoods to fisher families, partly a result of declining incomes in fisheries, nor the increasing threats to small scale fisheries from other competing uses of the coast such as industrialisation and tourism.

Nicolas Bautes and Ajit Menon