Great Yarmouth is a coastal town established by the Romans at the mouth of the River Yare (Yare-Mouth), in the East of England, which opens out into the North Sea. It was famous for herring fishing until the late 1970s, when following the industrialisation of the industry that led to the fisheries’ collapse, a fishing moratorium was introduced.

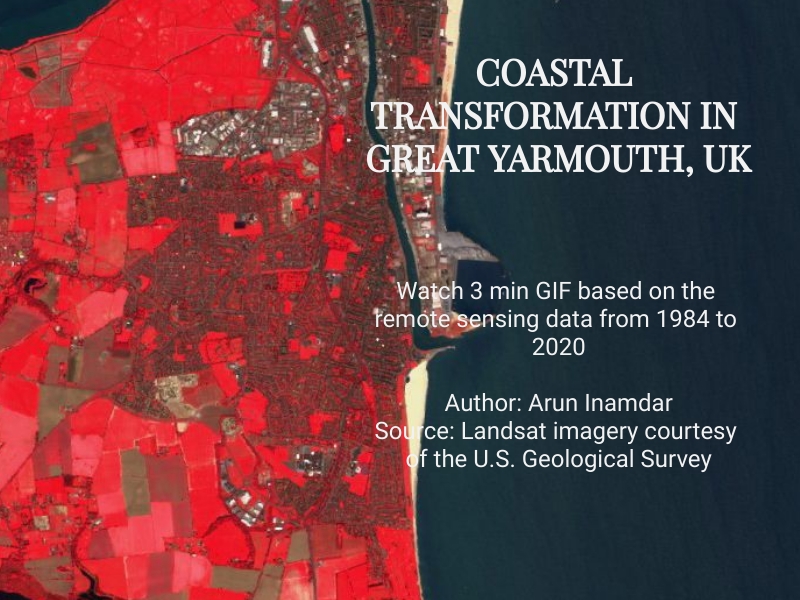

The ‘silting up’ of the estuary’s mouth created a sand bank that formed the origins of Great Yarmouth. Channelling was required for centuries to stop the harbour from being blocked due to increased sediment build-up until the man-made channel that exists today was dug from Gorelston. The satellite images show how sediments are still in flux today, with Scroby Sands – apparent offshore – moving with longshore drift. Today it supports a wind farm. The industrial development and growth of Great Yarmouth as a key port grew from its history of fishing and continued until the 1970s, with a sharp decline in the 1980s–90s before being replaced by an oil and gas industry, which had started to develop in the 1960s. As the satellite images show, the most obvious recent change in Great Yarmouth is the construction of Outer Harbour, a new deep-water harbour, which began in June 2007, motivated by the drive for expanding renewable energy schemes (wind turbines) nationally. The harbour has two breakwaters with a total length of approximately 1,400m. In November 2016, the outer harbour quays were strengthened to prepare for the construction of giant turbines from March 2017 as part of multi-million-pound wind farm projects. Climate change has serious implications for much of the area, which is vulnerable to flooding due to its low lying topography. Coastal erosion is also a persistent challenge that impacts the coastal landscape, with regular cliff erosion and periodic resettlement of people’s houses. Another future change is likely to arise through continuing recreational and tourist resort development and continuing demand for housing. Renewable energy development is likely to represent a key pressure on the landscape in the short to medium term, both on land and at sea, with some of the world’s largest offshore wind developments planned in the southern North Sea over the next decade.

Credit: Carole White