Using remote sensing images and GIS software with animations, this section of the on-line exhibition draws upon animated images of land-use change in coastal areas of India, Norway, the UK, and Slovenia. These animations tell stories of unchecked human influences on land use, tracing the degradation of land, coastal wetlands, marine resources, and displacement of coastal inhabitants.

Analysis of satellite images and scientific studies of ecological change often tends to be abstract, overly technical, and unintelligible to ordinary citizens and decision makers. This section uses animations to cast light on the significant adverse impacts of coastal transitions since the 1980s. Pointing to crucial impacts and future risks, they build narratives about so-called ‘development’ in coastal areas, which have come at significant human and environmental costs.

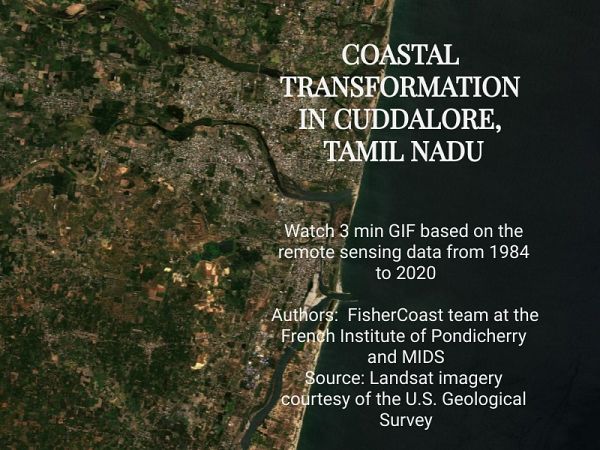

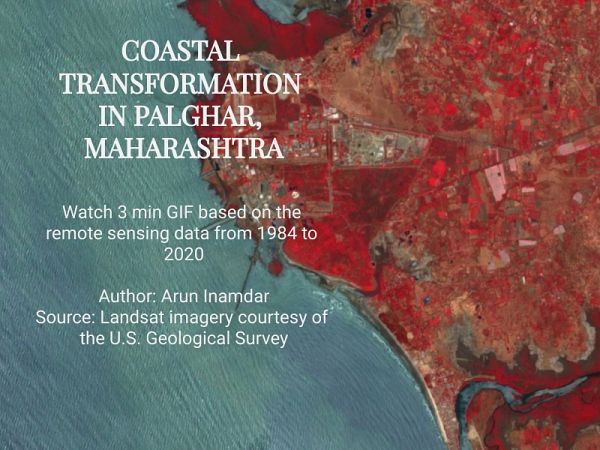

In India, there are two sites for the project – Cuddalore district on the east coast, and Palghar district on the west coast. Already buffeted by major changes in the fisheries, significant climate change-related risks from extreme events, and sustained industrial pollution, the continued well-being of coastal fishers in these districts is of serious concern. Deltaic and estuary changes, creek and river pollution, and coastal erosion with the rising sea level pose severe threats. The decline in the area under mangroves and coastal wetlands and the movement from natural to anthropogenic vegetation and built environment are common across the two sites.

Cuddalore, in the state of Tamil Nadu, has been strongly promoted as an industrial area. Privatisation of coastal commons on which fishers depend for their livelihoods and degradation of fragile coastal ecosystems have led to large-scale labour migration. The general decline of marine environments has overturned centuries of sustainable community-based natural resource management. Our animations display a fragmented landscape affected by pollution, land degradation, loss of vegetation, and urbanisation. Very evidently, the transformations adversely impacting small-scale fishers can be traced to patterns of industrial development, densification of urban settlements, and sedimentary flows from the dams on the Thenpennai River. Major geomorphological changes alter the entire coastline, putting at risk the coastal fishers who have made this region their home.

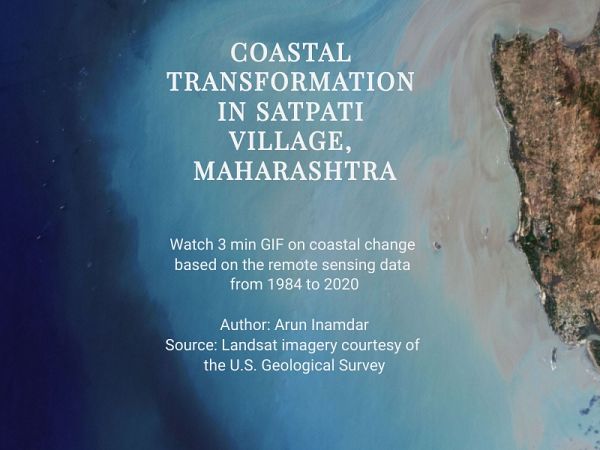

On the western coast of India, the district of Palghar shows the impacts of nuclear and thermal power plants and state-led industrial enclaves. India’s first atomic power plant, which started in the late 1960s, converted natural land cover to industrial and urban land; although the vegetation surrounding the power plant shows an increase in area, this is anthropogenic, not natural, with exotic species and monoculture that do not provide the same services and benefits that coastal wetlands and mangroves provide. One of India’s historic fishing villages, Satpati is located in this district. Famous for its boat building and pioneering fisher unions and cooperatives, the small-scale fisheries here are threatened by land-use change and coastal damages caused by fly ash from a thermal power plant, pollution from other industries, and the destruction of rocky outcrops to allow bigger vessels supplying coal to berth. Since the village is under the influence of tidal surge, flooding has become more frequent. Encroachment of creek banks and coastal wetlands for aquaculture hasdestroyed coastal biodiversity. Land degradation is seen as a likely key contributor to changing coastal geomorphology in the near future.

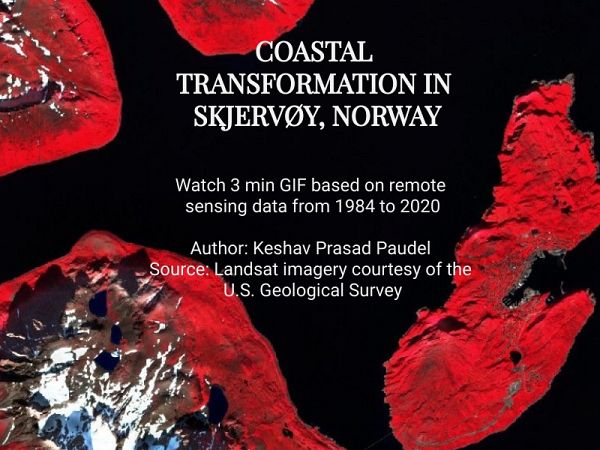

We then move to the Skjervøy, the administrative centre of the Skjervøy municipality, located in the northernmost region of Norway, long the location of traditional fishing communities, but now subjected to rapid physical changes and transformation of ocean and land resources. The animation from the mid-1980s shows the annual land-use change in the coastal and coastal marine spaces. In a context of depopulation, the expansion of ports and aquaculture has marginalised many of the fishing villages in Skjervøy. Infrastructure, industry, and tourism have supplemented the emergence of fish farms, metal and shipbuilding workshops, and fish processing to significantly change coastal land use. With global warming, vegetation is seen to be growing at higher levels. Simultaneously in the city of Tromsø, substantial shoreline change is observed. From the 1950s to the present, urban settlements and industrialisation have transformed land and ocean space, with known and unknown consequences for the future of these coastal regions.

Sediment flux and longshore drift have characterised the coastal transformation of Greater Yarmouth in the United Kingdom for centuries. Dating back to the time of the ancient Romans, and located on the North Sea, the city has witnessed industrialisation and the collapse of fisheries, affecting communities, public spaces, and the economy. The port development related to fisheries lasted until the 1980s to be replaced by oil and gas. A new deep-water harbour and a push towards ‘blue economy’ renewable energy projects have further transformed the coast by creating breakwaters and strengthening harbour quays. With severe vulnerability to flooding caused by climate change, and coastal erosion affecting physical landscapes, frequent population resettlement has become necessary. Future land-use changes, caused by tourism and housing development, may further marginalise fragile coastal environments in Greater Yarmouth.

In Slovenia, the animated GIF image is of the city of Koper, located on the northernmost part of the Mediterranean Sea. Once an island surrounded by the sea, the city has become a major industrial port, resulting in multiple coastal changes over several decades. The bay has disappeared both to human activities and silt deposits from the Badaševica and Rižana Rivers. Slowly the bay was converted into marshland and saltpans that were active until the beginning of the 20thcentury. As the port and its related infrastructure spread further hinterland in the course of the 20th century, large shopping malls and natural reserves contributed to further land use change.

Together, these animated GIFs tell a story of natural and human-induced coastal change, with apparent promise for socio-economic development but significant challenges for fishers’ wellbeing and future environmental risks.

D. Parthasarathy, Indian Institute of Technology Bombay